The Story of “Discovery”

Learning for Christians without Essays and A-Levels

1. How it began

In October 2002 I started work as priest in charge of St Peter’s Braunstone Park, a large outer urban council estate with multiple deprivation and a controversial New Deal for Communities programme that was trying to tackle the estate’s many problems. As well as getting to know the community and its many organisations and informal groups, I was beginning to see growth in the church – to some extent in numbers, but especially in spiritual life, and in the confidence and willingness on the part of a few individuals to minister personally to others. One woman, only recently confirmed, got out of her seat to put her arm round an elderly gentleman who had been overcome by emotion during our annual Remembrance Sunday service. That may not sound like much, but it was a new departure for St Peter’s and a breakthrough for Linda, as well as healing for the gentleman.

I began to discern in Linda a potential for pastoral leadership and wanted her to do some training, with a view to her being authorised for lay ministry by the wider church. But Linda, in common with many Braunstone residents, had no educational qualifications. She had left school at 15, being told by her teachers that she was stupid. I met many parishioners, inside and outside the church, who told me they had had the same message from their schools – “Oh, you live in Braunstone; you must be thick. So we’re not really going to bother with you…” Not surprisingly, three or four generations of “Braunies” responded by not really bothering with the education system, leading to one of the lowest educational attainment statistics in Leicester and even the UK. (I’m glad to say that the New Deal for Communities has had an impact on this state of affairs. But there is still a long way to go.)

My first clergy meeting in Leicester Diocese included a discussion about the Hind Report, which seemed to me, in my ignorance, to be aiming to make training for ministry in the Church of England more, not less, academic. This threatened to put it even more beyond the reach of the very people whom, I sensed, God was calling to minister in His Church. A year later I was invited to teach the Worship and Spirituality module in the diocesan basic lay training course, then called “Exploring Christian Life and Faith”. The co-convenor of my course, Pat Ward, was also vice-chair and treasurer of St Peter’s (and becoming a friend), and a member of the diocesan Black and Minority Ethnic campaigning group. She said to me, “You know, this course isn’t reaching ethnic minorities in the church,” and I reflected that no, it wasn’t reaching members of Urban Priority Area churches either. In order to cover six modules in a year, each module was squashed into half a term, which (with home reading and essays) required a great deal of academic confidence as well as discipline, and enough leisure to be able to make the course a top priority. Fine for university graduates, but not for most people in areas like Braunstone and churches like St Peter’s.

So we called a meeting of a few interested parties in St Peter’s. Along with Pat and myself, there were Chris Florance, community worker and educator, Ruth Souter, curate and “local lass”, full of insight into the local scene and immersed in the work of Unlock, formerly the Evangelical Urban Training Project – Roz my wife, trainee Reader and adult educator and trainer in her work, and Linda, without whose personal experience we would have gone nowhere. We shared our concerns and ideas, and then called another meeting, to which we invited Peter Burrows, then the diocesan director of training. The long journey had begun.

2. Values, ideas, methods

It took 2 or 3 years before we started to deliver any training, but the time we spent thinking it through was worth it. We shared what we considered our core values – these were:

• Excellence. Our potential participants are intelligent (if sometimes under-educated) and deserve the very best. We will not “dumb down” or patronise.

• Centred on learning rather than teaching. It’s not what we write or say, it’s what people learn that’s important. So the course will be experiential, rooted in participants’ context, and not book-centred.

• Valuing of people, their cultures and styles. For many (including some of the original core group) learning has been a negative experience, involving put-downs and even humiliation. We want to inspire confidence by affirming and encouraging our course participants.

• Releasing people to be themselves and minister to others. Learning is not just an end in itself (though it is valuable in itself, not least for the confidence it can impart). In Christian ministry it has an immediate practical outcome, and we want to enable people to use their learning, and to discover their own gifts and become confident to use them.

As we continued to meet, we invited a couple of vicars from other Urban Priority Areas in the city to join us. Alison Roche and Philip Watson are very different people (and different from us) and their insights and energy were an important addition to the mix. Peter Burrows left us to become Archdeacon of Leeds (he is now Bishop of Doncaster) and we invited not one but two of his successors to join us – Mike Harrison the Director of Mission and Ministry, and Stuart Burns the head of the newly set up School for Ministry.

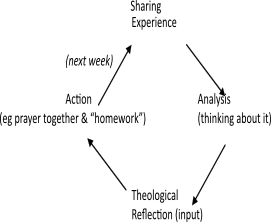

Two ideas shaped the way we devised the course material. The first was the Pastoral Cycle, developed by Paolo Freire in Brazil, which empowered many powerless people to deepen their Christian faith and, at the same time, to put that faith into practice in the struggle for social justice.

The process starts where participants are strong (their experience) – not where they are weak (book knowledge). This allows them to contribute positively throughout the process, and makes learning more important than teaching. It helped revolutionise the Christian formation of basic communities in the deprived urban areas of Latin America, and we believed it to be equally relevant to urban communities in Leicester.

The Pastoral Cycle

• Experience – sharing our stories, both good and bad

• Analysis – thinking together about what our experiences mean; making connections

• Theological reflection – the “input” stage, bringing an aspect of the Gospel to bear on our thinking (and making more connections)

• Action – putting our learning into action, leading to more experiences to share …

We resolved that each session would travel round the pastoral cycle, starting with the sharing of experience and moving through analysis and theological reflection to action. In practice some of the modules followed this cycle more closely than others.

The other idea was original to us. In my former parish in Leeds I had been part of a city-wide group set up by the archdeacon and UPAs officer to look at social justice and urban culture. The recently appointed diocesan UPAs officer produced a paper, which was then discussed mainly by the other clergy present, leaving those lay people (invited for their urban experience and wisdom) silent and marginalised. Suddenly my friend Joyce said into a silence, “Of course, it’s all jargon really, isn’t it?” Consternation! – but the other lay people’s mouths were opened too, and the whole conversation was transformed. Joyce and I were tasked with translating the document into plain English, and (while on holiday, accompanied as I remember by some red wine) we evolved a way of talking about it that led to a translation. Joyce would ask what a particular sentence meant, and I would try to explain it in plainer English. Then Joyce (who had a way with words) would say, “Oh, you mean …” and put it in a different way that made its meaning obvious. Then I would write that down, and we’d move on to the next obscure sentence or idea.

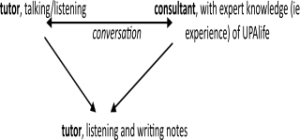

We adapted this bit of pastoral experience for designing the six modules we had decided to use as our basic structure. Each module design team would have an expert consultant, in other words someone who lived in an Urban Priority Area and was empowered enough to tell the clergy and tutors exactly how it is. There would be a conversation between her (or him) and a tutor, based on what Joyce and I had learned and done, and, as things became clear between them, a second tutor would write it down. In that way the course content was devised – though, looking back at the finished product, some module writing groups seem to have worked better than others.

Designing the modules – diagram

Preferred learning styles

We learned that people learn in different ways, and used the “VAK” analysis in our session plans to ensure a variety of learning methods. So, for people who learn best visually, there was plenty to see (illustrations, flip-charts etc), while for people whose preferred learning was auditory, there were loads of discussions and, in some sessions, songs or music. The third learning method was more challenging – kinaesthetic learners learn best by doing, moving or touching and feeling. So we looked for ways that participants could learn by doing, and in one particularly demanding session (prayer in the darkness, in Module 2) we deliberately introduced “praying with clay”.

The Six Modules, and their associated Study Skills – Moderation and Validation

The modules were based on the original diocesan course, which seemed to cover the sort of content that our people would want to learn something about. In addition, we wanted to help them learn some study skills that would help them in any future training.

One basic skill was keeping a “learning log”, which could include written notes, photos and even tapes of spoken material. Creative endeavours which would never be kept could still be photographed, and the prints kept as evidence of learning. These logs were handed in at the end of each module to the Head of the Diocesan School for Ministry, who would assess what each participant had learned and validate that learning, eg for future training on a diocesan lay ministry course. It was agreed early on that Discovery (completed over two years) would count as equivalent to the first, more intense, year of diocesan lay training.

Modules

1) You, me and God (together in Christ’s body – and something on confidence)

2) Coming closer to God (prayer and worship, including the Bible and the Dark Night of the Soul, and working together on a closing Eucharist)

3) Oh God, why? (Evil and the God of love, including the story of Ruth)

4) Jesus and the first Christians (New Testament)

5) Back to our roots (Old Testament)

6) Watch this space! (Mission in today’s world)

Study Skills in each Module

1) Learning log, presentation, discussion

2) Making connections, team work for liturgy

3) Creative listening

4) Finding your way round the New Testament *

5) Finding your way round the Old Testament *

6) Discerning vocation, yours and each other’s

* In Modules 1 to 3, we printed out the Bible passages – finding your way round a 1,000-page book is a study skill to learn later in the course.

The first course participants

The first 3 modules were finally ready, and we started with 5 course members in September 2006. One dropped out at Christmas (she had too much else in her life) and four people finished Module 3 in June 2007. We still had not written Modules 4, 5 and 6 by then, and there were 5 more people wanting to start. So we repeated the first 3 modules in 2007/8 with another group, and combined the two small groups to start Module 4 in Sept 2008, with a cohort of 8 (one more having dropped out). The first course graduated in June 2009.

3. Theological reflection

“Poured out on all flesh”

The theological idea for Discovery has been with me at least since the early 1970s, and comes from one of the effects of Pentecost – “The Holy Spirit will be poured out on all flesh” (Joel 2:28; Acts 2:17,18). Almost all religions have had their “special holy people”, whether priests or prophets, shamans, witch-doctors or wise women, who were believed to have special access to God or the gods, and who in consequence wielded considerable power that was attributed to them by the people. This can be seen even in the stories of the Old Testament (see, for instance, the story of Saul looking for his father’s donkeys in 1 Samuel 9.) So the prophecy in Joel 2 that the Holy Spirit would be poured out on “all flesh”, including both sexes, all ages and even slaves, was indeed to prophesy a radical new departure, a sign of the Day of the Lord. On the Day of Pentecost, Peter quoted the prophecy to point to current events as a sign of the Day of the Lord, the coming of the Kingdom of God. Ordinary people, fishermen and so on, were speaking languages they had not learned, proclaiming the works of God to pilgrims from all over the known world.

The disciples didn’t have an A level between them, but Jesus entrusted them with the worldwide mission of passing on the Gospel. Over the centuries, as the Church became more established and institutional, the power to teach (and even learn) was restricted to a priestly elite; then, after the Reformation opened learning up again, the professional preachers quickly took back the power to teach, and the ability to share learning was shut down again. The Anabaptists were known for their refusal to collude with this – they believed in and practised a multi-voiced teaching ministry, and included unlettered men and women, along the lines of Paul’s description in I Corinthians 14. This was shocking to one Lutheran spy, sent to infiltrate their meetings, and it is a matter of record that the Anabaptists were persecuted with equal enthusiasm by Catholics and Protestants alike.

Lay theology

The charismatic renewal, as I experienced it in the early 1970s, believed in and practised multi-voiced worship, in their prayer meetings if not their Sunday worship. Michael Harper articulated a theology for this in “Let my people grow” (Logos International, Plainfield, NJ; 1977) but not many charismatics at the time knew that similar ideas were proposed by J A T Robinson a decade earlier – “A New Reformation?” (SCM, London; 1965) where a Lay Theology was envisioned to replace previous loci of theological thought in seminaries and/or secular universities.

Resourcing churches in deprived urban areas

At the time of Discovery’s genesis (2003-6) churches in Urban Priority Areas (UPAs) were vulnerable to the economic argument that a retreating Church of England should concentrate on areas, and demographics, which were most likely to give a return for investment. To put extra effort and resources into deprived areas, where the church has been historically weak, is – so the argument goes – to throw good money after bad. Against that is set the Church of England’s historic mission to every parish in the country, and to every demographic. Further back in our founding theology is God’s own bias to the poor, seen throughout the Old Testament and assumed (and sometimes made explicit) in the pages of the New Testament.

My experience in Leicester Diocese has been positive in this respect – Bishop Tim Stevens (2000-2015) had a background in urban ministry, and was unfailingly supportive of clergy and churches in UPAs: he even appointed two successive archdeacons of Leicester with urban experience – Richard Atkinson (Sheffield and Rotherham) and now Tim Stratford (Liverpool and Kirkby). But I hear of other parts of the C of E where a more monetarist stance prevails, and inner city and outer estate churches are more or less left to sink or swim by themselves.

But even that sort of isolation doesn’t have to separate us from the love and power of God. Small struggling churches in hostile cultural environments go right back to the New Testament era – how can we learn from them to help our brothers and sisters to thrive in similar situations today? Surely one way is to train and encourage potential leaders to learn, and to pass on their learning, in a way appropriate to their culture.

So we set about devising training that would help us (2 or 3 small parish churches, and by extension others too) to move towards a Christian community that could learn, and teach, and minister in Christ’s name, in a cultural language appropriate to its setting. We haven’t got anywhere near that goal, but I do think the attempt has been worth making. And a small number of individual lives have been transformed, as we shall see below. The “Ark” project in estate parishes in northern Bristol has gone further in this – see the writings of Joe Hasler who worked there for many years.

4. Did it work?

The spirit in the first two pioneer groups was warm, co-operative, and life-enhancing. The participants had not expected to be allowed on to a course that gave them training in Christian ministry – such things are still unconsciously reserved for the clergy – and, with the emphasis in the first module on building confidence, even those who had been put down at school (like Linda) found themselves learning and achieving. The learning logs were helpful in this, as they allowed participants (with guidance) to record their learning in their own way. There were no essays, and no text-books except the Bible: even then we printed out the Bible readings for the first three modules – finding your way through a 1000-page book is a study skill to be learned, not something we assumed everyone could do confidently.

At the diocesan awards ceremony in October 2009, the bishop who had been invited to give out the prizes said, “This evening is the result of a huge amount of individual work.” He was probably right about those who had done the other, more academic courses, but I remember thinking that, as far as Discovery was concerned, he had missed the point. The awards were the culmination of a huge amount of shared work, of mutual help and encouragement, of laughter and tears at the sessions and between them, and of surmounting the immense cultural barriers that make it so much harder for people without academic education to succeed in completing a course. Some lasting friendships were made across different churches, and two participants went on to train as Pastoral Assistants. In St Peter’s Braunstone, where the course had started, the handful of church members who have done the Discovery course over several years have had a subtle but significant effect on the way we do things – not least the PCC, where a silent and compliant culture has changed into one where it is OK to express one’s opinion – and even OK to disagree with the vicar! Linda, with whom it all started, became PCC secretary while doing a catch-up English course at a local college. She trained as a Pastoral Assistant and is now convening the Pastoral Care Group in the church. Before she qualified, she was taken into hospital with bowel cancer, which (several years later) she has overcome with courage and a smiling, positive attitude.

Discovery has been run 4 or 5 times since that first pair of courses, and I acted as tutor for two modules in 2013-14. I was surprised that one of the study skills (creative listening in Module 3) did not feature – I altered the module (along with my co-tutor) to include it, only to discover that two of the participants (admittedly from more middle-class backgrounds) had done extensive listening training and didn’t see what the need was! Not all the modules followed round the Pastoral Cycle, and some of them were unbalanced in learning styles. If we had been more thorough in the initial module planning, we might have been more consistent. I wonder what effect that would have had in helping to transform the lives of our participants, especially those from UPAs. But after our initial enthusiasm and aspirations to thoroughness, other priorities crowded in and we ended up ruled more by deadlines than our values. I wonder whether there is energy among the UPA churches to revise the course?

One other limitation on the effectiveness of Discovery has been its take-up by UPA churches round the diocese. Most of the parishes who have sent participants have had clergy who were enthusiastic about lay training. That is only 5 or 6 parishes. Very early on, we had invited all the UPA clergy in Leicester to an introduction and taster session, to interest them in the potential of the course. Most did not come, and many of those that did, did not share the vision. But the future of the Church lies in leadership by local lay people, not by the fewer and fewer imported and professionally trained clergy. If we cannot find a way for emerging leaders in UPA churches to learn and to lead, those churches will die – or they will be replaced by more indigenous independent churches who begin with basic assumptions that are more open to the Spirit, poured out today as in the New Testament era, on all flesh.

this is really fascinating Chris and I’m so glad you sent me a copy. Just one important correction – Many people believe, as you say, that it was Paulo Freire who created the pastoral cycle but of course if you read his material he was not doing that at all.

What happened was that a number of us were working in Europe from the Young Christian Workers’ model of See/Judge/Act and then incorporating ideas that were being formed among the poor in our own work and especially in Latin America – The theologians there were putting a theoretical framework around what we were all finding was going in amongst the poor. It was here that the idea of the pastoral cycle was being offered by Guitierrez, Boff and especially Segundo.

I was then tutoring with the Urban Theology Unit and to help our students I decided to create a diagram to express where this was all up to. Because my background had been educational psychology I based it on the educational work of David Kolbe, and it was thus that the Pastoral Cycle diagram came to be.

So the diagram was a UK invention and I think it’s worth pushing this because this helps to pull our detractors away from the claim that it’s all a Latin American invention and not applicable to our scene. The fact is that it was born here!

Thanks, Bishop Laurie, for your comment – and for a bit of history I’d been quite unaware of. Put it there for the UK theological scene, for the Urban Theology Unit and, not least, for yourself!

Chris.